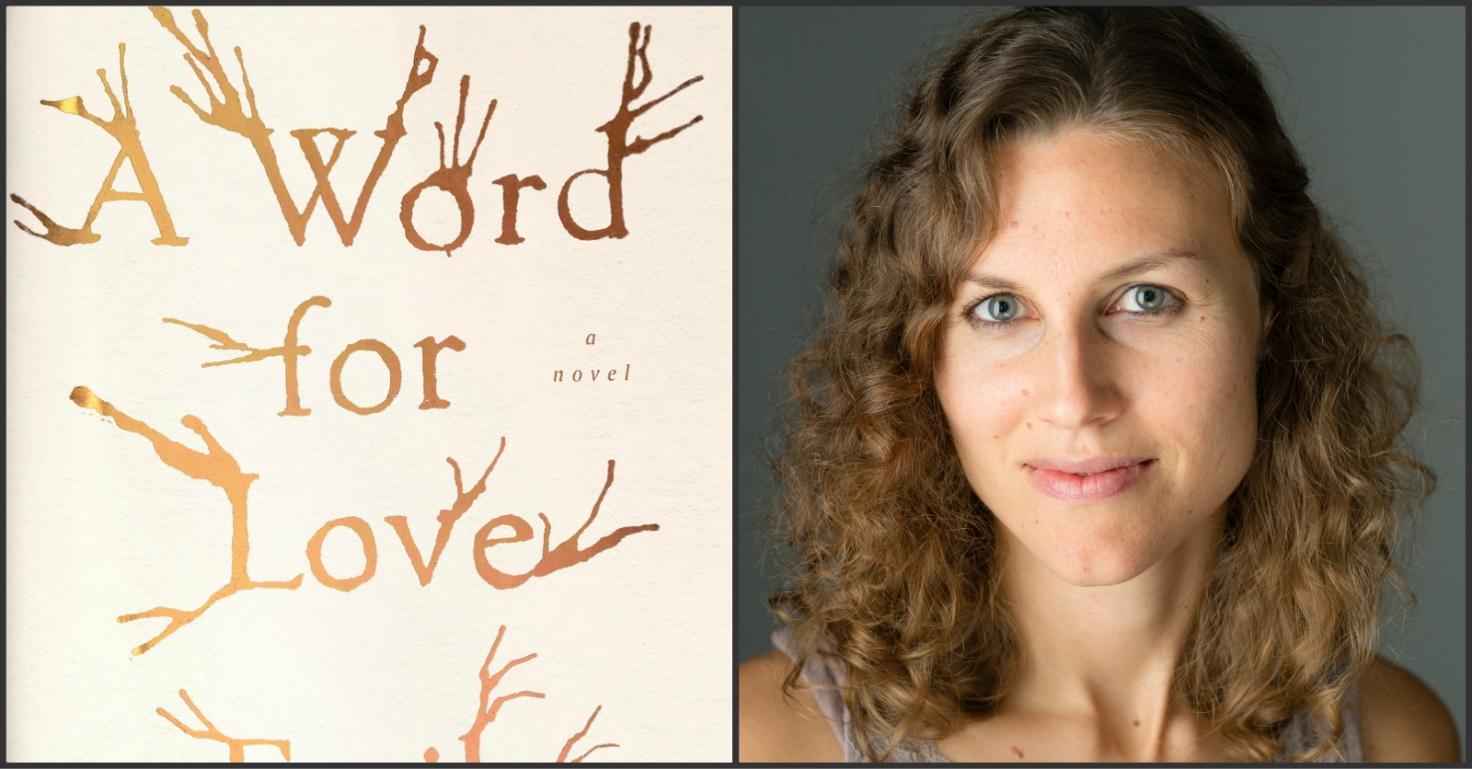

McCreight Fiction Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Emily Ruskovich is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she was my classmate, and was a James C. As Wade slips into dementia-with catatonic episodes that can turn violent-we, like his second wife, Ann, try to reconstruct, understand, and ultimately come to terms with the sorrowful events of the past. The novel centers around Wade, an Idaho man who has lost both his daughters when his ex-wife, Jenny, murdered one child, the other fled into the woods and disappeared for good.

Like “The Love of a Good Woman,” Idaho is a murder mystery-but the mystery is not who did it so much as so much as how, why, and with what consequence. Ruskovich explained how the story’s power, horror, and beauty derive from Munro’s restraint, and how its central image-a red box full of optometrist’s tools-becomes a powerful reminder of what’s missed when we move too quickly to look closely.

The dramatic plot includes a murder, a cover-up, the discovery of a body, a life destroyed by guilt-but the narrative proceeds with great discipline, revealing its secrets carefully over time. In her conversation for this series, Ruskovich discussed Alice Munro’s “The Love of a Good Woman,” a novella that begins in the least flashy way possible: on the musty shelves of a local museum, with drawn-out descriptions of the objects displayed there. (You know the kind of thing: “On the morning of the day my brother killed my father, I spent an hour unburying my truck from new snow.”) But Emily Ruskovich, the author of Idaho, teaches her writing students not to grab at the reader so directly-the technique, she says, tends to result in desperate, dishonest openings.

There’s a widely circulated truism that short stories should start with a spring-loaded “hook,” a can’t-miss-it first line that foregrounds conflict right away.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)